- Product

- Industries

- Law enforcement

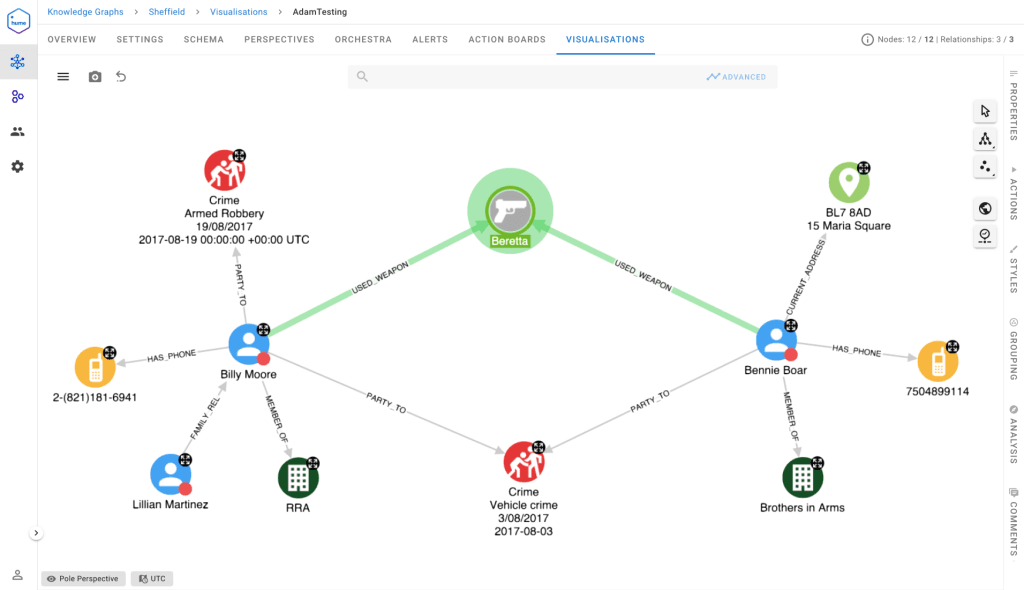

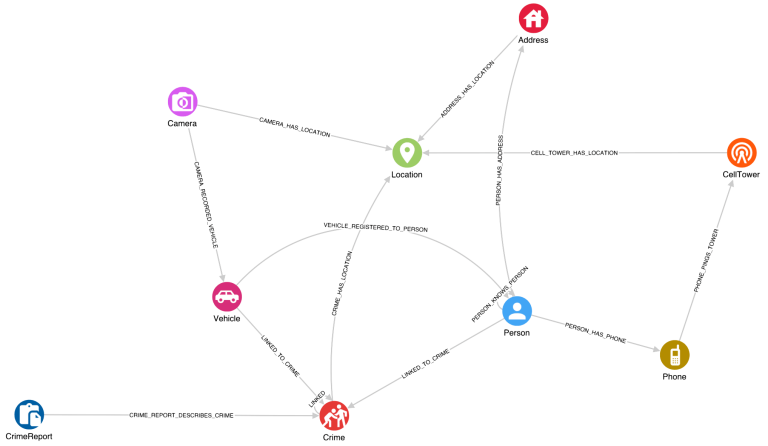

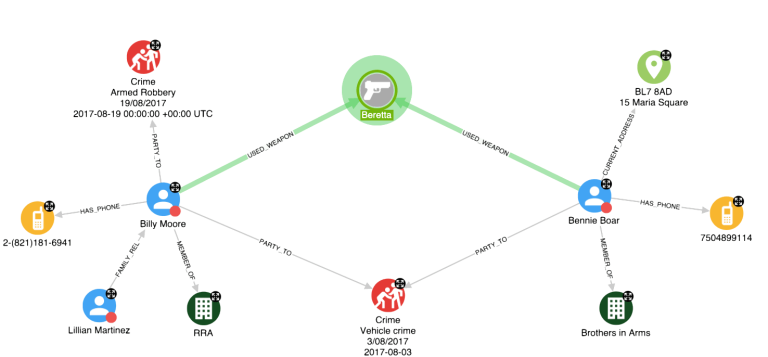

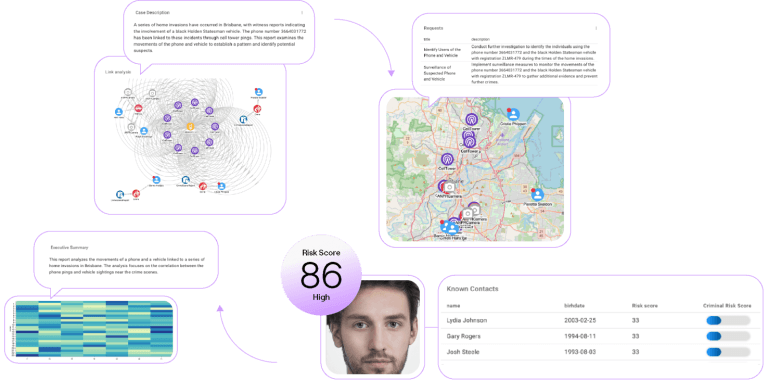

Leverage intelligence-led policing with mission-critical graph analytics capabilities.

- Financial authorities

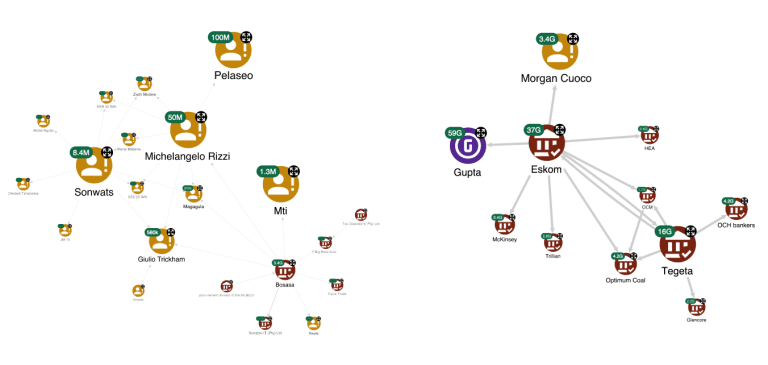

Gain capabilities to act quickly, stop fraud and protect your clients and your business.

- National security

Enable automation, learn about bad actors and their networks, and leverage predictive strategies.

- Law enforcement

- Case studies

- Resources

- Webinars

New use cases, features, and live demos designed to make analysts’ lives easier.

- Books & papers

Our research, philosophy and case studies, all wrapped up in books and papers.

- Videos

Discover GraphAware Hume’s features, demos, and graph technology insights.

- Events

Meet our team at conferences and events around the world.

- Documentation

Review our in-depth user guides and technical documentation to ensure flawless operations.

- Webinars

- Blog

- Company